Ancient Medicine

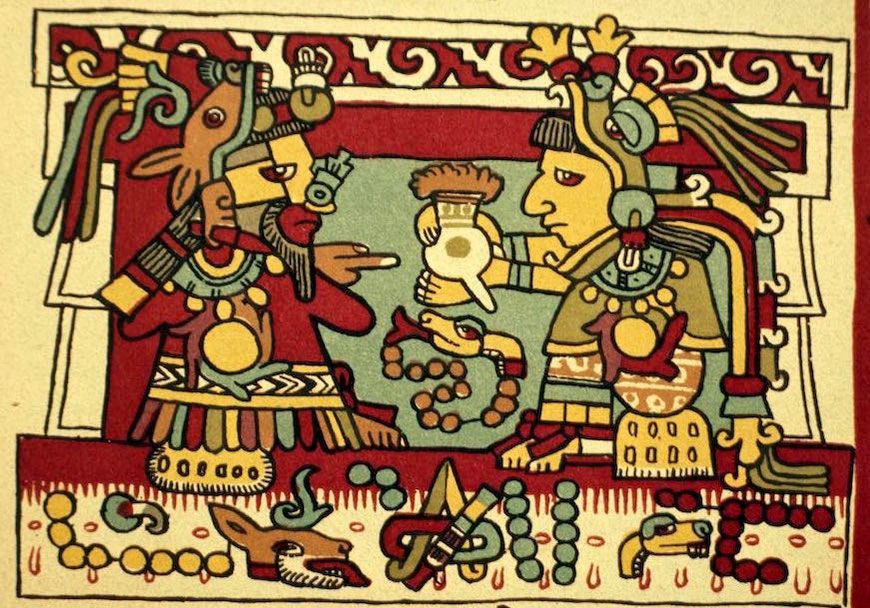

Mesoamerican Medicine

The land of ancient America offers a distinctive case study to examine the autonomous progress in non-Western societal contexts of therapeutic methods and techniques.

Medicine in Mesoamerican cultures commenced in the year 1,500 BC and ended with the Spanish conquering and destruction of Mexico-Tenochtitlan in 1521.

In the years following the conquest, the medical history of the ticiotl was restored from the works of Bernardino de Sahagún, Francisco Hernández, and the Cruz-Badiano codex.

All of these codexes outlined the use of plants and herbals in cures for disease, such as edema, urinary retention, kidney stones, and podagra.

Aboriginal medical systems and techniques conveyed the concepts of a holistic path to medicine – encompassing the mental, somatic, and spiritual equilibrium.

We find this association in all the medicinal systems of the ancient civilizations.

In Mesoamerica, the medical was generally known as ticiotl, which derives from the word tícitl - for physician.

The Aztec physicians knew countless illnesses well and were excellent healers of fracture and wounds.

The literature of modern historians acknowledges the position of ticiotl medicine.

History

The medicine of the Aztecas implied a sophisticated and philosophically articulated medical theory centered on the polarity of cold and warm, on spirituality, astronomy, and divination.

The boundaries between magic, faith, and empirical evidence for natural causes were not precise in their assumption of health and illness; therefore, they accepted the divine as possessing a significant influence in their existence: human or natural source of the diseases.

Many localized indigenous populations have contributed to a wide range of technical understanding and competence related to herbal, chemical, surgical, extra- somatic or ritual methods to medicine and public hygiene.

The database of ancient medical practices and techniques in America is as impressive as it is convincing.

A wide range of techniques are used in the medicinal field of Maya civilization but spread across all over the South American continent.

The practice of medicine had a very well-established system setting a very sophisticated structure of disciplines that enabled them to gain a vast knowledge in the managing of chronic and acute diseases in various stages of development.

Therefore, this medicinal system functioned with an integral procedure combining plant, animal, and mineral assets.

Gold played an important role in South America.

Gold was used along with other metal-based dental fillings, cranial trephination, postcranial

surgery, and coca-based anesthetics, to Mesoamerican

intramedullary nails, medicinal enemas, surgical sutures

and cauterization, cesarean sections, topical anesthetics, poultices, and birth control ( Mendoza; 2016 )

They developed a complex causal system, where they interpreted that the illnesses caused by the gods or heavenly spirits, were hot, whereas those caused by beings of another realm were cold.

The medical procedure was referred to as texoxotlaliztli, and its cures were named tepatiliztli.

The physician was named as texoxotlaticitl and created sophisticated methods in suture handling, injured, abscess drainage, fractures and joint dislocations, pterygium, tonsillitis, circumcision, and amputations.

Much of our knowledge of contact with medical practices is derived from the detailed chronicles compiled to document the cultural history of the Aztec and Inca civilizations ( Mendoza; 2016 ).

The medical anthropologists like Bernard Ortiz de Montellano (1990)

has classified the Aztec ideas on the symptoms and diagnosis of disease into three groups:

Religious or spiritual, magical, natural or physiological

He points out that the Aztec had a holistic perspective concerning the causes and cures of the disease.

Thereby, referring to the work of Mexican ethnohistorian, Lopez Austin: “the origin of illness is complex, including and often intertwining two types of causes: those that we would call natural – excesses, accidents, deficiencies, exposure to sudden temperature changes, contagions and the like – and those caused by the intervention of nonhuman beings or of human beings with more than normal powers. ( Mendoza 2016 )

For example, a native could think that his rheumatic problems came from the supreme will of Titlacahuan, from the punishment sent by the tlaloque for not having performed a particular rite, from direct attack by a being who inhabited a specific spring, and from prolonged chilling in cold water; the native would not consider it all as a confluence of diverse causes but as a complex” (Lopez Austin 1974: 216–217).

Of Aztec practitioners' medicines, herbal and chemical remedies were included, diuretics, laxatives, sedatives, soporifics, purgatives, astringents, hemostats, hallucinogens, anaesthetics, emetics, oxytocics, diaphoretics, and anthelmintics.

Herbal Medicine in South America

Aztec physicians had to balance herbal and other chemical treatments with interpretative correlation models varying from supernatural and magical to natural, or a complex mix of both.

The wide range of herbal knowledge associated with the Americas and eventually embraced by medical practices based in Europe included ancient Native American medicinal and hallucinogenic products such as coca (Erythroxylon coca), mescaline (Lophophora williamsii), nicotine (Nicotiana tobacco), quinine (Quina cinchona), psilocybin (Psilocybe mexicana), dopamine (Carnegiea gigantea), anodyne analgesics (Solandra guerrerensis), the ergot alkoloid D-lysergic acid (Ipomoea violacea), and genipen-based antibacterial agents (Chlorophora tinctoria).

However, there were also medicines and associated chemicals that delivered a spectrum of skills for Aztec physicians.

To display a few, N-dimethylhistamine to atropine, serotonin, tryptamine, kaempferol, prosopine, pectin, and camphor.

Furthermore, there was a variety of antibiotic or antiseptic treatments for treating wounds, medicating infections and fractures, and performing surgery.

These included the herbal vasoconstrictor comelina pallida, maguey or agave sap, for its hemolytic, osmotic, and detergent effects, hot urine in lieu of other available sources of sterile water, and mixtures of salt and honey which have been determined to provide enhanced antiseptic functions. ( Mendoza 2016 )

Surgical Practices

Pre-Colombian medical treatments had been extensive and advanced in the application, particularly those related to surgical methods.

According to the records of the colonial era, "Aztec combat physicians skillfully treated their injured and cured them quicker than the Spanish doctors ... [ and ] ... one aspect of evident Aztec supremacy over the Spanish was wound therapy."

European wound treatment at that time consisted of cauterization with boiling oil and reciting of prayers while waiting for infection to develop the ‘laudable pus’ that was seen as a good sign” (as cited in Ortiz de Montellano 1990).

Medical historian Miguel Guzman Peredo cites Fray Bernardino de Sahagun:

“Cuts and wounds on the nose after an accident had to be treated by suturing with hair from the head and byapplying to the stitches and the wound white honey and salt.

After this, if the nose fell off or if the treatment was a failure, an artificial nose took the place of the real one.

Wounds on the lips had to be sutured with hairfrom the head, and afterwards melted juice from the

maguey plant, called meulli, was poured on the wound; if, however, after the cure, an ugly blemish remained,

an incision had to be made and the wound had to be burned and sutured again with hair and treated with

melted meulli.”

A sophisticated typology was also maintained by the Aztec to display human anatomy and physiology.

They distinguished particular body parts, organs, and their associated biological functions and used anatomical definitions for the articular surfaces and attachments of the limbs, such as the words acolli, moliztli, maquechtli and tlanquaitl, for shoulder, elbow, wrist, and knee articulation, successively.

"These physicians had more than basic knowledge of the various organic features," according to Guzman Peredo.

For instance, they knew about blood circulation.

They also named tetecuicaliztli the throbbing at the tip of the heart.

Radial pulse was called tlahuatl.

Armed with such knowledge, the Aztec “used traction and counter

traction to reduce fractures and sprains and splints to

immobilize fractures” (Ortiz de Montellano, 1990).

Perhaps the use of the intramedullar nail is one of the most important medical innovations. Bernardino de Sahagun (1932) observed that bone fractures could not be cured “the bone is exposed; a very resinous stick is cut; it is inserted within the bone, bound within the incision, covered

over with the medicine mentioned.”

Western medicine did not rediscover the intramedullar nail until well into the 20th century.

Examples of the practice have been documented from

throughout South, Middle, and North America. An

extensive review of this practice can be found

elsewhere in the encyclopedia. ( Mendoza 2016 )

Trepanations

Trepanation is the scraping, cutting or drilling into an opening (or structures) of the neurocranium.

Despite the probability of brain injury, bleeding, and infection, trepanation in prehistoric times was amazingly common, dating back to 5000 BCE in Europe and around 500 BCE in the New World.

Tréphination (or trepanation) of the human skull is the earliest known human-made surgical procedure.

From the Neolithic age to the very origin of history, trephined skulls have been discovered by archeologists.

These surgical practices were valuable for medicine.

More than 1,500 trephined skulls were discovered worldwide, from Europe and Scandinavia to North America, from Russia and China to South America (especially in Peru).

Trephinations were conducted in children as well as adults, both men, and women

However, most trephinations were discovered in adult men.

Worldwide, a range of trephination methods has been used, including scrapping, carving, and both straight and curved skull grooving.

The head was selected for the operation, not because of any specific inherent significance or because of magic or religious purposes, but because of the distinctive and widely collected knowledge experienced during altercations and hunting by the ancient person in the Stone Age with pervasive head injuries.

We must remember that the much more advanced old Egyptians, Mesopotamians, Hindu, and even Hellenic cultures believed that the heart was the center of thought and feelings, not the brain.

In effect, the connection of the heart with emotions continued until this age.

Since most Neolithic skulls were not trephined, it denotes that the procedure was reserved for the most prominent male members of the group and their families ( Prioreschi P. 1991 )

I believe Prioreschi's hypothesis is valid and his thesis almost certainly correct, unless new evidence proves otherwise: Man in the Stone Age all over the world indulged in the ubiquitous practice of Neolithic trepanation for bringing back to life or effect the resuscitation (the act of “undying”) of prominent members of the group who were considered “dead” by their own primitive conception of death and dying from both serious illness or injury. ( Prioreschi P. 1995 )

We may infer from the fact that ancient medicine observed the influence of spirits.

We can speculate why shamans or witch doctors performed this skull surgery, but we can not deny that there may have been a significant cause to change human behavior.

They used trepanations methods for intractable headaches, epilepsy, animistic possession by evil spirits, or mental illness, expressed by errant or abnormal behavior could have been indications for surgical intervention prescribed by the shaman of the late Stone or early Bronze Age.” ( Faria MA Jr. 2013 )

In ancient cultures, it was performed for the alleged mystic or religious reasons (e.g., demonic possession) but also for the treatment of madness, severe headaches and other chronic ailments ( Paciaroni M, 2016 )

Trephination was an attempt to carry back to life those influential persons deemed vital to the group's survival in the Neolithic stage of human social development that the ancient surgeon believed was worth saving.

The operation (single or multiple drilled holes, mostly in the frontal or parietal areas) was performed with careful removal of bones, brain meninges and the brain itself.

The use of trepanation in Western medicine has its primary origins in Egyptian and Greek brain injury therapy methods.

The operation was performed frequently throughout the Middle Ages and beyond during the Roman Empire (Celsius).

In the second half of the nineteenth century, figures decreased significantly, parallel with the growing switch to hospital care.

References & Citations

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?cmd=historysearch&querykey=2

Medicine in Meso and South America | SpringerLink.

https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-94-007-7747-7_8765

[Surgical practice in the Mexican Empire].

Departamento de Cirurgía, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. andreshuesca@yahoo.com.mx

Unidad de Hemodiálisis, Hospital Mocel, México, D.F. México. jcp29@prodigy.net.mx

[The concept of illness and kidney diseases in Nahuatl medicine. Synthesis of Mesoamerican pre-Columbian medicine].

A history of medicine: primitive and ancient medicine.

Prioreschi P Mellen Hist Med. 1991; 1():1-642.

Prioreschi P. Omaha, Nebraska: Horatius Press; 1995. A History of Medicine. Vol. I: Primitive and Ancient Medicine; pp. 30–2. [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

Violence, mental illness, and the brain - A brief history of psychosurgery: Part 1 - From trephination to lobotomy.

Faria MA Jr Surg Neurol Int. 2013; 4():49.

Paciaroni M, Arnao V. Neurology and war: from antiquity to modern times. In: Front Neurol Neurosc. 2016;38:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000442562 [ Links ]

Kamp MA, Tahsim-Oglou Y, Steiger HJ, Hänggi D. Traumatic brain injuries in the ancient Egypt: insights from the Edwin Smith Papyrus. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2012;73(4):230-7. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1313635 [ Links ]

Gurdjian ES. The treatment of penetrating wounds of the brain sustained in warfare: a historical review. J Neurosurg. 1974;40(2):157-67. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1974.40.2.0157 [ Links ]

Tsermoulas G, Aidonis A, Flint G. The skull of Chios: trepanation in Hippocratic medicine. J Neurosurg. 2014;121(2):328-32. https://doi.org/10.3171/2014.4.JNS131886 [ Links ]

Tulio E. Trepanation and Roman medicine: a comparison of osteoarchaeological remains, material culture and written texts. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2010;40(2):165-71. https://doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2010.215 [ Links ]

Gross CC. Trepanation from the paleolithic to the internet. In: Arnott R, Finger S, Smith CVM, editors. Trepanation: history, discovery, theory. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger B.V; 2003. p. 307-22. [ Links ]

http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0004-282X2017000500307#B13

http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0004-282X2017000500307#B13

Full text of "Medicine across cultures [electronic .... https://archive.org/stream/springer_10.1007-0-306-48094-8/10.1007-0-306-48094-8_djvu.txt

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a192/4f94c8d700e372ebf3081da6146e8d90c229.pdf

- Home

- Somatic Archeology

- Halotherapy

- Cranio-Sacral Therapy

- Chelation Therapy

- Diabetes Therapy

- Colon Hydrotherapy

- Magnetic Field Therapy

- Hypnosis

- Kinesiology

- Oxygen Therapy

- Lymphatic drainage

- Enzyme therapy

- Detox Therapy

- Cryotherapy

- Reflexotherapy

- Body Wrap Therapy

- Colon Hydrotherapy

- Ancient Chinese Medicine

- SPA Treatments

- Visceral Manipulation

- Pelotherapy

- Services

- Our Proposal

- Human Infrastructure

CenterforAncientAlchemyandTheHealingArts

Copyright © 2022 CenterforAncientAlchemyandTheHealingArts - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy Website Builder